Saturday, August 16, 2008

Sunday, August 03, 2008

Friday, July 25, 2008

Biking the 29th - A voyage of discovery - Across South Africa on motorbikes

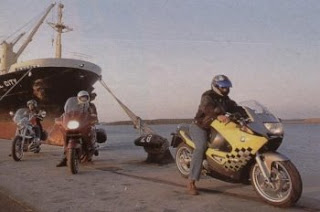

In Richards Bay, at the end of the long ride, we found a beautiful singer named Tracy in a bar. We asked her to play Yellow Brick Road for us, but instead she played Chris Rea's Road To Hell. Perhaps it was a warning. . . .

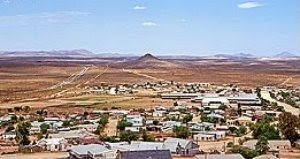

It began in Port Nolloth. The main road out of town heads east and is as straight as a map line. On either side is nothing but tussocky flat sand edged by faraway hills; Springbok lies straight ahead.

My BMW 1100 RT was going so fast it would probably be an offence to even publish the speed, and I found myself chuckling over a story about diamonds which Grazia de Beer had told me earlier that morning.

She has a little guesthouse called Bedrock, but used to run an eatery called Mama's Italian Trattoria. One day the waitress rushed in yelling that two strangers from up north were beating up her boyfriend outside the chemist. Grazia spied the unfortunate fellow tied, spreadeagled, in the back of a bakkie, which drove off at speed.

It seems the victim had committed the greatest crime of this frontier town - he'd stolen someone's diamonds by swallowing them. The angry pair wanted them back. They went into the chemist for a purgative, but couldn't speak any language the assistant knew so, from their frantic actions, he presumed Immodium was required. It turned the boyfriend's innards to concrete.

The police were notified and found all three out in the dunes, waiting for the reluctant diamonds to emerge. They were all arrested and the last Grazia saw of the boyfriend, by then fed with a stiff purgative, was in a hospital bed surrounded by policemen also waiting for the diamonds to appear.

That's Port Nolloth talk, which is always about diamonds and usually about IDB (illicit diamond buying). We'd spent the previous evening in the cosy Pirate's Cove restaurant trying to guess who the smugglers were.

* * *

* * *The adventure had actually started back in Cape Town in that casual way adventures often do: "Why don't we bike the 29th parallel?"

"Why the 29th?"

"Well, because it's the widest part of South Africa."

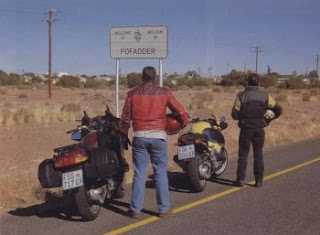

Somehow the fact that the line went through Springbok and Pofadder settled the matter. A few months later - on a bitingly cold midwinter day - we were astride three large, sensual machines with our backs to the icy Atlantic and our faces towards the warm Indian Ocean on the other side of the continent.

With the freezing wind creeping down our necks on the long ride up from Cape Town the whole idea, not to mention the timing, seemed crazy. But as the BMWs snaked up the Aninaus Pass towards Steinkopf and Springbok I found myself singing an old favourite of mine from the film Easy Rider: "Get your motor running, back out on the highwaaay, lookin' for adventure, or whatever comes my way. . . ."

With the freezing wind creeping down our necks on the long ride up from Cape Town the whole idea, not to mention the timing, seemed crazy. But as the BMWs snaked up the Aninaus Pass towards Steinkopf and Springbok I found myself singing an old favourite of mine from the film Easy Rider: "Get your motor running, back out on the highwaaay, lookin' for adventure, or whatever comes my way. . . ."This was going to be cool.

* * *

The bikes created a minor sensation outside the Springbok Café. "Juss," exclaimed a slightly tipsy pavement patroller, "where are you guys going?"

"Richards Bay."

"Where's that?"

"Where the sun rises."

He looked impressed.

Jopie Kotze is a legend in this part of the world and his Springbok Café is the meeting place for all manner of characters. We found the man behind a counter strategically placed to allow him a view of his café, restaurant, bookshop and gem collection. He was not fazed by our black leathers and helmets and hauled out a bottle of petrol-tasting mampoer. "It'll keep you warm," he chuckled.

Behind him was a pair of boxing gloves which once belonged to Robey Leibbrandt. Their owner was an Olympic boxer in the 1930s and stayed on after the games in Germany, becoming a fanatical Nazi supporter. He returned, dramatically, by yacht and landed on the Namaqualand coast, making his way to the Transvaal where he set up sabotage units. He was caught, jailed, later released and settled in Springbok, still a hero to many.

Behind him was a pair of boxing gloves which once belonged to Robey Leibbrandt. Their owner was an Olympic boxer in the 1930s and stayed on after the games in Germany, becoming a fanatical Nazi supporter. He returned, dramatically, by yacht and landed on the Namaqualand coast, making his way to the Transvaal where he set up sabotage units. He was caught, jailed, later released and settled in Springbok, still a hero to many.On the wall nearby was a plaque to Jopie from the Namaqualandse Boerjode (Jewish farmers) with thanks.

"I'm a man in the middle," shrugged Jopie when I queried his wall display. "I like history and people like me. And I don't do IDB, I do gemstones. For me the diamond is not a pretty rock."

* * *

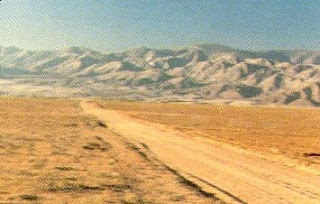

The N14 from Springbok to Pofadder was almost dead straight. It passed through treeless, seemingly endless scrub desert and was both terrifying and awesomely beautiful. Vehicles on the road were so few and far between that drivers waved to each other reassuringly as they passed.

I edged the bike onto the white line and had the strange sensation of being in a space-time warp. Under a dome of blue on a sea of yellow desert, the black ribbon of road ran like a line drawn from my front tyre to infinity.

The only imbalance was the telephone poles which, because of the absence of trees, served as supports for occasional large nests of sociable weaver birds or roosts for pale chanting goshawks. This sure was a great big country. . .

As we neared Pofadder I became aware of a movement behind some low hills on the horizon: a ghost-like figure seemed to be pacing our movement. I considered the possibility that the hypnotic symmetry was getting to me when the form seemed to solidify and resolved itself into a gigantic full moon rising over the rim of Namaqualand. Like the star of Bethlehem it led us to the little town of Pofadder.

There was room at the inn.

The Pofadder Hotel had doilies everywhere: big, small, square, round. In the winter months, when things are quiet, hotel owner Nella Britz turns one of the lounges into a sewing bee and teaches her staff to embroider doilies.

"They need something, you know," she commented, "there's not much going on here between seasons." Her parrot, Vicegrip, rang his bell in agreement. Even he appears on the doilies, his image picked out in bright thread, and as we set off to the pub to play a game of pool I could almost swear he made the noise of a motor bike. Smart bird.

"They need something, you know," she commented, "there's not much going on here between seasons." Her parrot, Vicegrip, rang his bell in agreement. Even he appears on the doilies, his image picked out in bright thread, and as we set off to the pub to play a game of pool I could almost swear he made the noise of a motor bike. Smart bird.The road continued out of Pofadder the way it came into it: dead straight. But it was soon relieved by strange dolerite extrusions which looked like giant molehills. They were stark evidence that our continent floats on a liquid magma sea which appears occasionally in millions-of-years-old rock spouts.

By the time we picked up signs for Kakamas the limb-warming alcohol of the previous evening was beginning to take its toll so we swung off the N14 to take a break at Augrabies Falls on the Orange River.

"You are now entering a WARZONE against chaos, crime, laziness and poverty," a large signboard informed us. We rode on, nonplussed, and ordered tea and plates of chips at the restaurant beside the falls. The river was running at a mere five percent capacity, but it still plunged with a mighty roar into the gorge. The Bushmen considered the place to be haunted, and they had a point.

Beyond Kakamas the scenery changed dramatically as the road snaked up through tough-looking hills and past farms watered by the Orange River. I stopped at a roadside stall to buy some dates but I had to ask the assistant where they were: they were so big I hadn't recognised them. I rolled into Upington like a hamster, my cheeks stuffed with their delicious flesh.

Beyond Kakamas the scenery changed dramatically as the road snaked up through tough-looking hills and past farms watered by the Orange River. I stopped at a roadside stall to buy some dates but I had to ask the assistant where they were: they were so big I hadn't recognised them. I rolled into Upington like a hamster, my cheeks stuffed with their delicious flesh.* * *

In the past the wooded islands around Upington were strongholds for river pirates, bandits, rustlers, renegades and desperadoes. The infamous Captain Afrikaner had his hide-out there, as did his lieutenant, a Polish forger named Stephanus who had escaped while awaiting execution in Cape Town.

The celebrated highwayman, horse thief, rustler and adventurer Scotty Smith also settled in Upington, where he died of Spanish flu in 1919.

The celebrated highwayman, horse thief, rustler and adventurer Scotty Smith also settled in Upington, where he died of Spanish flu in 1919.All this seemed to have rubbed off on the traffic cops. One pack lay in wait for speedsters just outside town, another ticketed one of the bikes for touching a yellow line beside a parking bay and our faithful Maui camper, trundling along behind us, received another ticket when a parking meter expired while we sipped coffee at the Wimpy.

The town undoubtedly has its good points, including some BMW enthusiasts who came to shoot the breeze about bikes, but we back-tracked to Kanoneiland to look for a bed and supper. The place really is an island, right in the middle of the Orange River, and was named because of a battle there between river pirates and a police contingent in 1879.

The school on the island closed down some years ago and has been converted into a guesthouse called Cannon Island Tourism. With a braai sizzling and beers in hand we explored the place and, in the school courtyard, found the cannon that had been used to bombard the island during the battle.

Getting up next morning was hard work: it was freezing. Despite good leather gear the breeze cut like a knife - I was thankful the bike had heated handle grips and I blessed its clever designers.

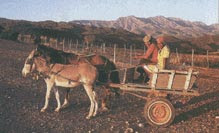

Back at Upington we diverted onto the N10 and near Grootdrink we came across Agus Rots who was making headway behind the steady tow of one donkey and one horse power. He was incredibly thin and wizened and his wagon badly battered.

He didn't seem too sure where he was headed - or even where he'd come from - and when we offered to send him a photo of himself he did not know where we could send it. So we asked his two grandchildren to write down their address, but they couldn't write and didn't have an address. Karretjiemense are the gypsies of South Africa, probably descendents of the Bushmen, and the road is their home. But in the far-flung emptiness of the Northern Cape it seemed a desolate existence.

* * *

At Groblershoop we turned east again and, as the road wound through some worn-looking sandstone mesas, the red dunes of the Kalahari slid across the horizon, glowing in the sinking sun. As we rolled into Griekwastad it was party time. We cut the engines on a hill overlooking the little town and the thump of inchoate rhythm and roar of voices floated up to greet us. Then a throbbing, coppery moon popped up to join in the fun.

At the café in town it was quieter and we found vivacious, blonde Tania, dreaming of a boyfriend in New Zealand. We also discovered the gentle hospitality which was to endure right across the Platteland. We were served coffee and offered food - which was a surprise since most South African cafés are just grocery shops.

Over a large plate of hot chips we discovered that just round the back was The Little Guest House. It was absolutely charming, with en suite bathrooms, lounge and dining room.

Mary Moffat, daughter of missionary-extraordinaire Dr Robert Moffat, was born in Griekwastad in 1821. When the young David Livingstone set eyes on her he was smitten and they were soon married. Poor Mary had a hard life, either trekking across untamed Africa, ministering to the sick or awaiting her husband's return from his travels. It's hardly surprising she turned to the bottle for solace.

There's a museurn in the town dedicated to the lady and it's well worth a visit. In it, among many missionary things under the care of curator Hetta Hager, is a pulpit from which Moffat preached. She says his ghost used to deliver angry sermons from the pulpit until she put a metal gate across the museum door.

We left the town in a haze of windswept dust. The road stretched out languidly across a featureless plain covered with vaalbos and sweet-thorn. Judging from the frequent road signs and black skid marks, the main inhabitants of the area are kudu devoid of road sense. At night these large antelope with pogo-stick tendencies will try to leap over your lights and land right on top of you. I watched the verges with eagle eyes.

In Campbell, a hamlet a bit further down the road, we came upon Livingstone's Church. It had a stark new concrete floor, no pews, bird droppings everywhere and was sadly bare. A plaque outside read: "In memory of David Livingstone, the great African explorer." If the church is anything to go by, that memory is fading. We shrugged, kicked the bikes back into life, and hit the empty road.

Most people think the wind, noise and vibration are the source of the biker's exhilaration. But after 30 minutes of wind you feel no wind, after an hour of noise you hear no noise.

The vibration is slight but numbing. The wind, noise, and vibration seem to cancel each other. And in that vacuum between yourself and what's going on in the surroundings, you hang in limbo, seeing only what you want to see, feeling what you want to feel, cushioned by your thoughts and the transformation of time.

* * *

Kimberley, when it finally appeared over the table-flat horizon, was a bit of a let-down. We decided to visit the Big Hole and hunt up some lunch. The Historical Village has been carefully reconstructed, and the museums were fascinating, but the food at the so-called restaurant was appalling. In fact the whole area had a slightly sad feeling. The hole was, well, big - very big - and there's evidently an even larger one on the other side of town.

I guess we didn't really give the town a chance, but it felt good to get back on the road. Around that time it occurred to me we were becoming road junkies - as bikers often are - the roar of the exhaust and the blur of tarmac being more compelling than any destination.

Motorbikes hardly touch the road and keeping them on it at speed requires intense concentration. With a car-sized engine between your legs a slight spin of the wrist can slam your body backwards as the machine accelerates to speeds seldom considered by drivers of four-wheelers. Bikes are about freedom, speed . . . and flying.

When Boshof appeared, though, it was time to stop. It's a cute little Platteland town among the mealie fields but hardly the place you'd expect to find a first-class meal and elegant accommodation. But both were at hand.

The Gompie Café offered a fine meal and The Boshof Arms Guest House, run by Cynthia and Doug Greig, couldn't be faulted: we even got hot-water bottles. After a gargantuan breakfast the next morning we pulled the bikes onto their lawn for a wash-down. Stroking our iron steeds, we found, was a good way to get to love them.

* * *

From there it was a long leap across the feverishly busy N1 highway towards Bethlehem. Just before the town the implacable Platteland began to heave uneasily and, as we crested a rise, its demise was written clear across the horizon in the jagged mountains of the Drakensberg. The bikes gave a throaty roar of delight as the road dipped and climbed towards Clarens. This was the kind of terrain big touring bikes love.

It often snows in Clarens but we were spared the pleasure. It was freezing cold, though, and it took several sherries beside the fire at Maluti Mountain Lodge to thaw out our stiff joints.

Golden Gate awaited us early the next morning. In the crisp dawn light the road snaked away from beneath our tyres like a long black tongue, leading us into the red, gaping gullet of an immense mountain serpent. The looming sandstone walls glowed with living intensity and a lammergeier, that giant, golden vulture with flaming red eyes, wheeled above us, seeming to watch our every move.

If the Great Sculptor created the Platteland in a moment of boredom and the Drakensberg as an act of passion, she undoubtedly paused in Golden Gate to play.Biking through the beetling cliffs is an extraordinary experience, but connecting up with the busy N3 between Gauteng and Durban was a nightmare. Cars, taxis and road-repair vehicles jostled for position down Van Reenen's Pass and it was a relief to turn off towards Ladysmith and Dundee.

Night was falling as we entered Dundee - it was an unscheduled stop; we'd hoped to get a little further. A cafe owner directed us to the Bergview Lodge which turned out to be a sort of traveller's motel. A high steel gate and equally high wall surrounded the place and at 23h00, we were told, they let out all seven dogs. Buks and Isobel Viljoen welcomed us from behind a long bar.

* * *

Crossing the Buffalo River east of the town the next day was like skipping between two worlds. On the Dundee side were fenced farms with swathes of yellow grass, on the other was peasant Africa-hut clusters, unfenced cattle, waving children, busy pigs, sleepy donkeys and projectile sheep hurtling across the road.

Driving was dangerous but interesting, and all the concentration brought on a mighty thirst. So did the heat: KwaZulu-Natal was ignoring winter. Stan's Pub in Babanango came just in time.

Stan Wintgens is something of a legend and he claims his pub to be the smallest in South Africa. He's run the place for 25 years and it was certainly the most cluttered I'd ever seen, with 'stuff' ranging from flags and caps to women's underwear and a small wooden rabbi with an erection. The underwear, he explained, had to be taken off in the pub. The toasted sandwiches came promptly and the cider hit the counter cold and most welcome. Stan was fun.

From Babanango the road deteriorated as it snaked down through forest plantations. The giant logging trucks have potholed the road and the yawning traps in the tarmac surface forced us to weave around dangerously at times.

As the sun dipped low we picked our way along a confusion of roads towards Richards Bay. The dream had been to skid up to a beach beside the warm Indian Ocean, throw off our clothes and plunge into the breakers shouting: "We've done it!"

As it turned out all roads seemed to lead to the vast harbour and we couldn't find the beach. We couldn't even find the town until the next morning, and it turned out to be the sort of place that probably looked good on the drawing board of some town planner but had no soul.

To console ourselves we decided to spend our last night at the rather fancy Richards Hotel. The bikes looked distinctly out of place in the parking lot and highly polished luxury cars frowned rudely at our dusty camper.

Inside, the place was more welcoming and we found the beautiful Tracy Payne in full song at the bar where we ordered a round of celebratory whiskys. She had a great voice.

"We've biked all the way across the continent," we called to her. "Sing us a song." The ballad she toasted us with had a fine blues rhythm, but it seemed a little unfair to choose Chris Rea's number The Road to Hell. Perhaps she knew something about the place.

Somehow Richard's Bay wasn't working for us. The next morning, as we picked our way out of town - having abandoned the beach plan - we came upon a crowd of chanting demonstrators. One held a banner saying "We don't approve of conditions." We didn't either, but by then we were confirmed road junkies: the destination didn't matter, the joy was in the travelling.

As we hit the N3 for the final run to Durban we cranked our throttles and watched the speedometer needles climb. It felt good to be back on the road again . . . whether it led us to heaven or to hell.

- republished from Getaway magazine, October 1998. Pictures by David Bristow and Don Pinnock.

The Ultimate Ride

I cut my biker’s milk teeth on the Chapman’s Peak road, eighteen years ago. The first time I rode the Peak was on a little Garelli 50 – a Supersport, mind. Later on I had a successions of Bonnevilles, Lightnings and Commandos, but I never got near learning everything that road had to teach me. And not only about riding bikes, either.

The first time I came to London I made friends with a biker named John. John and I had some good raps about bikes. Neither of us had a bike then because we were too poverty-stricken. But we could still talk, and one night I told John all about Chapman’s Peak and the good feelings I’d had riding bikes on it. The Ultimate Ride, I called it.

‘Maybe we’ll ride it together some day,’ John said. It was just talk because the Peninsula and riding a bike on Chapman’s Peak seemed very far away that winter’s night in suburban London.

‘It’s summer there now,’ I said.

The road was built by Italian soldiers, captured by South Africans troops in Ethiopia and the desert during WW2 and sent to labour camps in South Africa. They built it well. The approach to the Peak are easy enough and no more difficult than any other coast roads on the mountainous Peninsula. But the main section is carved out of about three miles of rather sheer cliff, more than 1 000 feet above the sea. The road there is a succession of tight corners, often steep, and it’s bordered all the way along on the sea side by a stone parapet. But the surface isn’t always in good shape. There are usually road workers around somewhere. The whole area, road and all, is a nature reserve. You often see animals there: baboons. buck, rock rabbits, sometimes even a porcupine.

The Cape is one of the floral kingdoms of the world and the mountain vegetation is special. A square yard of good Cape mountainside probably contains more varieties of plant than the whole of the British Isles. So, the mountains are protected and there’s no picking flowers, no lighting fires except at the special picnic spots along the scenic drives including the Peak. And at the picnic spots there are signs warning of the danger of fire. The signs don’t help much. There are fires every dry season anyway. There are other signs along the Peak road, too. You find several of them, all on the steep section, warning in words and pictures of falling rocks. These signs don’t help much either. John and I often talked about the Danger of Falling Rocks, especially that winter when the Peninsula lived up to it’s original name of the Cape of Storms, with weeks of gales and cloudbursts fit to loosen the rocks above the road. Every time we rode the Peak we’d have to steer round piles of rubble on the tarmac. Some were quite big rocks, other powdered by the impact of a long fall…

One day a rock fell on to the road about 20 feet in front of where I was driving. It bounced over the parapet and tumbled down the cliff to the sea. It was about a foot across, that rock. Some weeks later a huge boulder flattened the rear section of a delivery van, but it missed the cab and no-one was hurt. We heard tales from neighbours, long-time residence at Noordhoek, who told fearful tales of rockslides, but they were all narrow escapes. There were no stories of serious injuries or deaths caused by those Falling Rocks on the signs.

But there had been plenty of other deaths there on the Peak road. The summer before a biker on a big Honda had a head-on with a VW Kombi. He died. In the autumn rains some idiot drove a stolen MGB straight over the parapet. The car plunged hundreds of feet down the cliff before something stopped it. It was completely wrecked. Police and mountain club people spent two days searching for a body, but then he gave himself up at a police station. He hadn’t been hurt at all; he’d been flung out of the car near the top and climbed back up to the road to hitch a lift back to Cape Town.

Some time after a heavy biker arrived from Johannesburg on an immense Harley Super Glide. He got drunk one night at one of the beachfront hotels, staggered outside, straddled his bike, kicked into life and roared off straight past the sign that say To Chapman’s Peak. Moving fast, he plunged straight off at the first corner, bounced off some rocks and landed in a small bay that belongs to a holiday resort down there. He only broke a leg, and they even patched his Harley up for him. Tough beasts, the pair of them.

I remember one special ride. It was an autumn afternoon. It had rained earlier, but now the sun was out. I was riding home from my job in the city. There wasn’t much traffic about and there were still some wet patches left by the rain. Some of the corners were slippery. I had a close encounter with a manhole cover just as I was coming out of a corner slightly wetter than I’d judged it to be, and an interesting slide on a patch of gravel that a truck had spilt on another corner, probably while he was having troubles of his own.

I decided to race the sun – to see if I could get to the top of the Peak before it set – then I’d have a good view to take in while I stopped and had a smoke. The Trident handled well and had plenty of smooth power, and as I straightened up and accelerated out of the corners into the short straights, then changed down again, leaning into another corner, then up and over the other way… it seemed to me that I was vertical and bike was stationary. It was the road, the world, that was whirling under me like this, up and down, from side to side, rushing straight at me, then just blowing in my face as it swept past.

I didn’t see any of the signposts, just the tarmac in front and the roadsides blurring past the edge of my vision. Sometimes I took the chance of a neck-twisting glimpse up at the mountains soaring above me, or down at the sea crashing into the rocks hundreds of feet below. The bike and the road and me and this world rushing at us: I was right into it, fused into this action sequence, my body and senses, my instincts, my brain turned right in, all systems working smoothly. It wasn’t quite clear where I ended and the Trident began, or where the bike ended and the road started. And the road doesn’t end, you just leave it for a while now and then…

You walk from the parking space down a few steps to a safely-railed lookout point. If you climb over the rails and clamber down the rocks a bit, and then turn sharp left, you find yourself in a cave directly over the sea crashing into the foot of the cliff a thousand feet below. A much better lookout point, and that’s where I sat and smoked, watching the sunset, feeling like a mountain eagle in its eyrie. I threw a rock into the sea and climbed back up to the road, geared up again, started the Trident and rode on, feeling quite different, very relaxed and easy. I went through the switchback of cliffhanger corners fast and smoothly, not going too close, but not shying away either, and taking time on the short straight that just gives you the time for a first glimpse of the beach to notice that the lagoon was full again. There’d been a spring tide…

And no rocks fell on me. Falling Rocks didn’t even enter my mind. But they always entered John’s mind on that road.

Like another afternoon when we were going home together over the Peak in a car. John was driving, and we were talking about something or other. We passed East Fort, where there are some old cannons which used to command the bay when the Dutch owned the Cape and the manganese mine in the last century.

‘Yes, but only when the weather’s bad.’

‘The wind’s blowing.’

‘But there hasn’t been any rain for a while to loosen the rocks.’

‘No, but still.’

‘John, are you really scared of being hit by a rock that just happens to plunge down Chapman’s Peak and land at just that very spot and at that precise moment when your head happens to be underneath it?’

‘It could happen.’

‘The odds are remote. You do other things all day that are much more high-risk without even thinking about it – I mean you owe a bike for instance. But you can’t come along this road without the thought crossing your mind that you might get hit on the head by a Falling Rock.’

‘Don’t you think about it? You nearly got hit once.’

‘I think if I got killed by a rock while riding on Chapman’s Peak, well that’d be it, it’d be my time. Only the Angel of Death or someone like that could get such dynamic timing together. No use trying to dodge, no use worrying about it. Look, there goes another one.’

‘Another what?’

‘Sign.’

‘Oh. I don’t worry about it, but the thought of it happening always comes to mind round about here on this road, whether I want it to or not. It’s not just the signs. It’s the thought that counts.’

We laughed.

‘Look, it’s my rock and I’ll think about it if I want to,’ John said, and laughed again.

‘Telekinesis or something…’

‘But still, he said a bit later, ‘this us definitely a high-risk road.’

‘Ultimate Ride, though.’

‘Yes, sometimes I wonder just how ultimate.’

And as the months went by John started using the other route to the city more often, over Silvermine Pass and along the motorway. He said it was quicker for him where he worked in southern suburbs. Also you don’t get any rockfalls on Silvermine pass. He still rode the Peak, especially when the weather was good and there was no wind or rain. But he didn’t commute that way anymore, not usually.

One evening about half of us at the Noordhoek house were getting dinner together in the kitchen. The other half, including John, hadn’t come home from work yet. Everyone seemed happy. Then the telephone rang, and Dee, John’s lady answered it. And then everything changed. We heard this terrible wailing, and we rushed to find Dee was doing it and the telephone was hanging there at the end of its line. It was all a very bad scene after that.

One evening about half of us at the Noordhoek house were getting dinner together in the kitchen. The other half, including John, hadn’t come home from work yet. Everyone seemed happy. Then the telephone rang, and Dee, John’s lady answered it. And then everything changed. We heard this terrible wailing, and we rushed to find Dee was doing it and the telephone was hanging there at the end of its line. It was all a very bad scene after that.John had ridden his Desmo straight off one of the high corners on the Peak. He’d crashed into the parapet and he and the bike both gone flying over it and down the cliff. John was killed. He died somewhere on the way down. There was a small pile of rubble in the road round about where John would have gone out of control. It was impossible to say whether John or the bike had been hit, but I guess he had – by his special rock. I still rode the Peak after that, and I still didn’t think much about Falling Rocks. But every time I got to John’s corner I’d think about him and his rock. John’s corner.

‘John’s Corner,’ I heard myself say one day as I reached the place. Now I’d named it, and naming it changed it for me. It wasn’t the corner where my friend John crashed his bike and died, now it was somehow the corner that killed John – John’s Corner. And it seemed to leer at me, as if I’d guessed its guilty secret. But wait, just you wait, maybe next time…

I really don’t usually think like that. I didn’t even think like that then, really, it was just an impression. But a strong one, and it left a bad taste. I don’t usually take any notice of feelings like that either – it was only a stretch of road, after all. A dangerous stretch, but no more dangerous then than it had been in all those years.

I really don’t usually think like that. I didn’t even think like that then, really, it was just an impression. But a strong one, and it left a bad taste. I don’t usually take any notice of feelings like that either – it was only a stretch of road, after all. A dangerous stretch, but no more dangerous then than it had been in all those years.Yet I also started using Silvermine Pass and the motorway, which is in way the Ultimate Ride. But the motorway was fast, and I was giving Anne, one of the girls at the house, a lift to university most days, and you don’t need a passenger much on the Peak.

I only rode the Peak once more after that touch of the Fear, and this time I got a Fear of the Fear, which is just distracting, and you don’t need distractions much up there either.

And it leered me again.

Anyway, even the Ultimate has its limitations.

- Fiction by Keith Addison, Republished from Bike magazine, UK, 1979

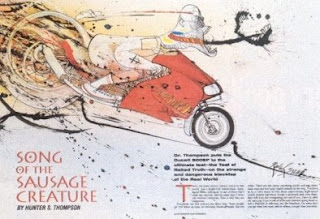

- Fiction by Keith Addison, Republished from Bike magazine, UK, 1979Song of the Sausage Creature

Everybody has fast motorcycles these days. Some people go 150 miles an hour on two-lane blacktop roads, but not often. There are too many oncoming trucks and too many radar cops and too many stupid animals in the way. You have to be a little crazy to ride these super-torque high-speed crotch rockets anywhere except a racetrack -- and even there, they will scare the whimpering shit out of you.... There is, after all, not a pig's eye worth of difference between going head-on into a Peterbilt or sideways into the bleachers. On some days you get what you want, and on other, you get what you need.

Everybody has fast motorcycles these days. Some people go 150 miles an hour on two-lane blacktop roads, but not often. There are too many oncoming trucks and too many radar cops and too many stupid animals in the way. You have to be a little crazy to ride these super-torque high-speed crotch rockets anywhere except a racetrack -- and even there, they will scare the whimpering shit out of you.... There is, after all, not a pig's eye worth of difference between going head-on into a Peterbilt or sideways into the bleachers. On some days you get what you want, and on other, you get what you need.When Cycle World called me to ask if I would road-test the new Harley Road King, I got uppity and said I'd rather have a Ducati superbike. It seemed like a chic decision at the time, and my friends on the superbike circuit got very excited. "Hot damn," they said, "We will take it to the track and blow the bastards away."

"Balls," I said. "Never mind the track. The track is for punks. We are Road People. We are Cafe Racers."

The Cafe Racer is a different breed, and we have our own situations. Pure speed in sixth gear on a 5,000-foot straightaway is one thing, but pure speed in third gear on a gravel-strewn downhill ess turn is quite another.

But we like it. A thoroughbred Cafe Racer will ride all night through a fog storm in freeway traffic to put himself into what somebody told him was the ugliest and tightest decreasing-radius turn since Genghis Khan invented the corkscrew.

Cafe Racing is mainly a matter of taste. It is an atavistic mentality, a peculiar mix of low style, high speed, pure dumbness, and overweening commitment to the Cafe Life and all its dangerous pleasures.... I am a Cafe Racer myself, on some days -- and many nights for that matter -- and it is one of my finest addictions....

I am not without scars on my brain and my body, but I can live with them. I still feel a shudder in my spine every time I see a Vincent Black Shadow, or when I walk into a public restroom and hear crippled men whispering about the terrifying Kawasaki Triple.... I have visions of compound femur-fractures and large black men in white hospital suits holding me down on a gurney while a nurse called "Bess" sews the flaps of my scalp together with a stitching drill.

Ho, ho. Thank God for these flashbacks. The brain is such a wonderful instrument (until God sinks his teeth into it). Some people hear Tiny Tim singing when they go under, and others hear the song of the Sausage Creature.

When the Ducati turned up in my driveway, nobody knew what to do with it. I was in New York, covering a polo tournament, and people had threatened my life. My lawyer said I should give myself up and enroll in the Federal Witness Protection Program. Other people said it had something to do with the polo crowd.

The motorcycle business was the last straw. It had to be the work of my enemies, or people who wanted to hurt me. It was the vilest kind of bait, and they knew I would go for it.

Of course. You want to cripple the bastard? Send him a 130-mph cafe racer. And include some license plates, so he'll think it's a streetbike. He's queer for anything fast.

Which is true. I have been a connoisseur of fast motorcycles all my life. I bought a brand-new 650 BSA Lightning when it was billed as "the fastest motorcycle ever tested by Hot Rod magazine." I have ridden a 500-pound Vincent Black Shadow through traffic on the Ventura Freeway with burning oil on my legs and run the Kawa 750 triple through Beverly Hills at night with a head full of acid.... I have ridden with Sonny Barger and smoked weed in biker bars with Jack Nicholson, Grace Slick, Ron Zigler, and my infamous old friend, Ken Kesey, a legendary Cafe Racer.

Some people will tell you that slow is good -- and it may be, on some days -- but I am here to tell you that fast is better. I've always believed this, in spite of the trouble it's caused me. Being shot out of a cannon will always be better than being squeezed out of a tube. That is why God made fast motorcycles, Bubba....

So when I got back from New York and found a fiery red rocket-style bike in my garage, I realized I was back in the road-testing business.

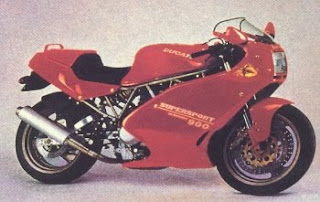

The brand-new Ducati 900 Campione del Mundo Desmodromic Supersport double-barreled magnum Cafe Racer filled me with feelings of lust every time I looked at it. Others felt the same way. My garage quickly became a magnet for drooling superbike groupies. They quarreled and bitched at each other about who would be first to help me evaluate my new toy.... And I did, of course, need a certain spectrum of opinions, besides my own, to properly judge this motorcycle. The Woody Creek Perverse Environmental Testing Facility is a long way from Daytona or even top-fuel challenge sprints on the Pacific Coast Highway, where teams of big-bore Kawasakis and Yamahas are said to race head-on against each other in death-defying games of "chicken" at 100 miles an hour....

No. Not everybody who buys a high-dollar torque-brute yearns to go out in a ball of fire on a public street in L.A. Some of us are decent people who want to stay out of the emergency room, but still blast through neo-gridlock traffic in residential districts whenever we feel like it.... For that we need fine Machinery.

Which we had -- no doubt about that. The Ducati people in New Jersey had opted, for reasons of their own, to send me the 900SP for testing -- rather than their 916 crazy-fast, state-of-the-art superbike track racer. It was far too fast, they said -- and prohibitively expensive -- to farm out for testing to a gang of half-mad Colorado cowboys who think they're world-class Cafe Racers.

The Ducati 900 is a finely engineered machine. My neighbors called it beautiful and admired its racing lines. The nasty little bugger looked like it was going 90 miles an hour when it was standing still in my garage.

Taking it on the road, though, was a genuinely terrifying experience. I had no sense of speed until I was going 90 and coming up fast on a bunch of pickup trucks going into a wet curve along the river. I went for both brakes, but only the front one worked, and I almost went end over end. I was out of control staring at the tailpipe of a U.S. Mail truck, still stabbing frantically at my rear brake pedal, which I just couldn't find.... I am too tall for these New Age roadracers; they are not built for any rider taller than five-nine, and the rearset brake pedal was not where I thought it would be. Midsize Italian pimps who like to race from one cafe to another on the boulevards of Rome in a flat-line prone position might like this, but I do not.

I was hunched over the tank like a person diving into a pool that got emptied yesterday. Whacko! Bashed into the concrete bottom, flesh ripped off, a Sausage Creature with no teeth, f-cked-up for the rest of its life.

We all love Torque, and some of us have taken it straight over the high side from time to time -- and there is always Pain in that.... But there is also Fun, in the deadly element, and Fun is what you get when you screw this monster on. BOOM! Instant takeoff, no screeching or squawking around like a fool with your teeth clamping down on your tongue and your mind completely empty of everything but fear.

We all love Torque, and some of us have taken it straight over the high side from time to time -- and there is always Pain in that.... But there is also Fun, in the deadly element, and Fun is what you get when you screw this monster on. BOOM! Instant takeoff, no screeching or squawking around like a fool with your teeth clamping down on your tongue and your mind completely empty of everything but fear.No. This bugger digs right in and shoots you straight down the pipe, for good or ill. On my first takeoff, I hit second gear and went through the speed limit on a two-lane blacktop highway full of ranch traffic. By the time I went up to third, I was going 75 and the tach was barely above 4,000 rpm...

And that's when it got its second wind. From 4,000 to 6,000 in third will take you from 75 to 95 in two seconds -- and after that, Bubba, you still have fourth, fifth, and sixth.

Ho, ho.

I never got into sixth, and I didn't get deep into fifth. This is a shameful admission for a full-bore Cafe Racer, but let me tell you something, old sport: This motorcycle is simply too goddamn fast to ride at speed in any kind of normal road traffic unless you're ready to go straight down the centerline with your nuts on fire and a silent scream in your throat.

When aimed in the right direciton at high speed, though, it has unnatural capabilities. This I unwittingly discovered as I made my approach to a sharp turn across some railroad tracks, saw that I was going way too fast and that my only chance was to veer right and screw it on totally, in a desparate attempt to leapfrog the curve by going airborne.

It was a bold and reckless move, but it was necessary. And it worked: I felt like Evil Knievel as I soared across the tracks with the rain in my eyes and my jaws clamped together in fear. I tried to spit down on the tracks as I passed them, but my mouth was too dry.... I landed hard on the edge of the road and lost my grip for a moment as the Ducati began fishtailing crazily into oncoming traffic. For two or three seconds I came face to face with the Sausage Creature...

But somehow the brute straightened out. I passed a school bus on the right and then got the bike under control long enough to gear down and pull off into an abandoned gravel driveway where I stopped and turned off the engine. My hands had seized up like claws and the rest of my body was numb. I felt nauseous and I cried for my mama, but nobody heard, then I went into a trance for 30 or 40 seconds until I was finally able to light a cigarette and calm down enough to ride home. I was too hysterical to shift gears, so I went the whole way in first at 40 miles an hour.

Whoops! What am I saying? Tall stories, ho, ho.... We are motorcycle people; we walk tall and we laugh at whatever's funny. We shit on the chests of the Weird...

But when we ride very fast motorcycles, we ride with immaculate sanity. We might abuse a substance here and there, but only when it's right. The final measure of any rider's skill is the inverse ratio of his preferred Traveling Speed to the number of bad scars on his body. It is that simple: If you ride fast and crash, you are a bad rider. If you go slow and crash, you are a bad rider. And if you are a bad rider, you should not ride motorcycles.

The emergence of the superbike has heightened this equation drastically. Motorcycle technology has made such a great leap forward. Take the Ducati. You want optimum cruising speed on this bugger? Try 90 mph in fifth at 5,500 rpm -- and just then, you see a bull moose in the middle of the road. WHACKO. Meet the Sausage Creature.

Or maybe not: The Ducati 900 is so finely engineered and balanced and torqued that you can do 90 mph in fifth through a 35-mph zone and get away with it. The bike is not just fast -- it is extremely quick and responsive, and it will do amazing things.... It is a little like riding the original Vincent Black Shadow, which would outrun an F-86 jet fighter on the takeoff runway, but at the end, the F-86 would go airborne and the Vincent would not, and there was no point in trying to turn it. WHAMO! The Sausage Creature strikes again.

There is a fundamental difference, however, between the old Vincents and the new bred of superbikes. If you rode the Black Shadow at top speed for any length of time, you would almost certainly die. That is why there are not many life members of the Vincent Black Shadow Society. The Vincent was like a bullet that went straight; the Ducati is like the magic bullet that went sideways and hit JFK and the Governor of Texas at the same time. It was impossible. But so was my terrifying sideways leap across railroad tracks on the 900SP. The bike did it easily with the grace of a fleeing tomcat. The landing was so easy I remember thinking, goddamnit, if I had screwed it on a little more I could have gone a lot further.

Maybe this is the new Cafe Racer macho. My bike is so much faster than yours that I dare you to ride it, you lame little turd. Do you have the balls to ride this BOTTOMLESS PIT OF TORQUE?

That is the attitude of the New Age superbike freak, and I am one of them. On some days they are about the most fun you can have with your clothes on. The Vincent just killed you a lot faster than a superbike will. A fool couldn't ride the Vincent Black Shadow more than once, but a fool can ride a Ducati 900 many times, and it will always be bloodcurdling kind of fun.

That is the Curse of Speed which has plagued me all my life. I am a slave to it. On my tombstone they will carve, "IT NEVER GOT FAST ENOUGH FOR ME."

- by Hunter S. Thompson, republished from Cycle World magazine, USA, March 1995

- by Hunter S. Thompson, republished from Cycle World magazine, USA, March 1995- The Gonzo King has passed away...

Girl with the black cowboy boots

She walks bare feet on the wet beach-sand

with her black cowboy boots in her hand.

Her dress clings to her hips in the salty breeze.

With a dead cigarette in her mouth she sighs at the horison.Water encircles her feet, calling her in...

I ride. Nothing in my wallet. Nothing in my heart.

Her footprints behind her wash away.

She looks up to see a man riding by on his gleaming iron.

Heads turn. Children stop playing.

She wants to call but he turns the bend.

And only the roar of his ride echoes through the corridors of her memory.

I have my denims and my leathers.

And space for a girl with black cowboy boots.

She stands on the edge of the cliff

where she climbed when the voices grew too loud

and stares at the end of the sea.

She laughs and empties the bottle of champaign into her mouth

as she realises she has never rode through the streets of Rome

or see the Arc de Trompe on a snowy winters day.

My rumbling horse takes me anywhere. And nowhere.

The empty bottle of champaign tinkle against the black cowboy boots

on the rhythm of the wind

that carried her into the waves

as she wondered what lies at the end of the sea.

I ride. Steel bars in my grip. Wind in my face.

(inspired by the road-movie Thelma & Louise)

Scared Brick

I am a brick in a wall

One of many

Together we are a wall

We keep the roof

We house life

Therefor, we are life

We are not alone

We are a wall in a house

A house in a street of many

Streets that keep families

Families that make communities

And communities live

Therefor we live

I am not alone

I am just a brick with a scar

And like many others

Like me

I am part of the wall

Just like others

Not like me

Not like us

Awakening

if I do not know why I am here

how I got here

what I did

It does not matter

if I do not know why I am not there

why I did not get there

what I did

All that matters

I am here now

My new life starts now

As it will tomorrow again

As it did yesterday too

All that matters

Is not my broken past

Or promising future

It is this moment that I breathe

Making it work for others and me

And God smiling upon us all

All that matters is now

Because the moment works fine

So the future is already fulfilled

And the past a useful memory

A road story

It is a scorching day in the Karoo next to the stretch of black tar that snakes through the dry hills, and anonymous cars flash by in a whirl of wind and metal. The stage is set for one of America’s finest to come by and mark this afternoon as something special. That sound is definitely old-school; I can hear the sidedraught gulping lung-fulls of clean Karoo air. That lazy throb that eminates from deep in the belly of a... What will it be? Panhead? Knucklehead?

I’ve been hitching for a few days now. I am dirty, thirsty and bored. And I can’t wait to get a lift on whatever it is that will come over that hill. Surely, a rider on such a soulful machine will have a kind heart?

It’s a she. Her long dark hair blows around her face from underneath the helmet. She gears down, blip the throttle and smiles at me as she stops. Heading somewhere cowboy?

Sure, wherever you are going. I could not believe my luck.

There is only one trouble, boy.

What is that?

It’s a single seat. Better luck next time.

With a rev and another smile she leaves me in her dust.

I thought it was too good to be true.

Damn, itsa scorcher today.

Old posts

I should resign more often. Not only is the workload and stress gone, but I now have time to surf the web and relax.

These items were written a very long time ago, as the dates on some of them show. Before my blog, I had a website. The pieces from that website.

Bikes that stood out

Aprilia Mana (scooter technology in a bike that works brilliantly)

Aprilia Street Triple 675 (small, light, characterfull)

Aprilia Daytona 675 (as above with added aggression)

Buell 1125 (ugly as hell, but the performance-price ratio is unbeatable for a twin)

BMW F650 (2008) (small and friendly, yet fun and exciting)

BMW K1200GT (no wonder the K1200R and S feel compromised. This is the real K12)

Ducati Desmocedici (I am the first local journalist to ride a MotoGP replica!)

Ducati Sport 1000 (a riot on two wheels)

Ducati 996SPS (A dream come true. This bike got me into biking)

Kawasaki ZRX1200 (old school technology have no right to be so much fun)

Harley Davidson Streetglide (Beat this: filtering through peak hour traffic with Linken Park on the speakers)

Harley Davidson Nightrod Turbo (Lighting Rod) (fast and serene. And I like the VROD anyway)

Honda Fireblade RR8 (handles like a 600)

Suzuki GSX-R750 (balance with a capital B)

Triumph Bonneville Speedmaster (the freeflow pipes made all the difference)

Yamaha R1 (the only Japanese bike to have soul and charisma)

Scooters

Suzuki Burgman 650 (it’s a better tourer than a BMW R1200RT!)

Jonway Spray 125 (the only Chinese scooter I could 120kph on!)

Worst (not counting the Chinese cheapies)

Aprilia Shiver (awkward handling and fuelling. How did it get past quality control?)

BMW R1200S (heavy, heavy, and compromised as a sportsbike and tourer)

Buell Lightning XB12S (ditch the Harley motor for something that revs, and will make sense)

What have I learned

The first thing that jump up is negative I am afraid. I have always vowed to never work for a big corporation. I lost sight of that vow for my dream job. I leave TopBike with the sense that everything I was told, assumed and read about corporations are true. Soulless, uncaring places where only a particular kind of person thrives that I better not mention. I need a more supportive, creative and dynamic environment, and for most of it, I was always able to work in such a place. Of course, not all corporations are heartless, but they sure are not plenty around.

What have I learned? Of the top of my head, that things are not what they seem. It seemed like a glamorous job, riding bikes all day long. Truth is, riding bikes is a very small part of the job. What you see in the magazine is the result of a lot of cursing, swearing, begging and threatening. And no, not the people who’s bikes it is, the people who pay your salary. From the first day I walked in it was a battle to get resources and support to do my job. And it only got worse as time went on.

It is impossible to make people understand why I leave, because they are blinded by the glamour. From my side, there is no glamour. It is simply a perception.

What was the highlight of my 18-month stint at TopBike. Without a doubt, that 8-day sprint on Jonway 250cc scramblers through Namibia and Botswana. It is the best trip of my live. Period. I consider myself fortunate, because it is such an unlikely adventure, no one else will ever do it, least of me again.

And the worst? That silly day on the mini-moto bike. Racing, crashing, being last. It was horrible. I wanted to pack up and go home. My thumb is still sore 6 months after the crash.

I am glad I had the chance to do my dream job. Otherwise I would forever wonder what it would have been like. Now I know. The myth is gone.

The Dream ends

I consider myself lucky to be able to walk away from a job, into another one I like. I have always been blessed in that regard. Not everybody can afford to just walk out. I suppose there is something to be said for finding the endurance to stay on in a job you don’t like. Am I just arrogant? Why won’t I?

I don’t see it as the end of my biking publishing career though. I will just go back to freelancing, as I have done before, but since I am known to the industry now, it will be far easier to get published. I will do the stories for the fun of it, without the under-resourced, ulcer-inducing, anxiety-driven exercises it has become with Topbike. I look forward to having my weekends back for myself, and being able to see my friends more often again. And I will be able to blog regularly again!

On a more positive note, I am leaving on good terms, so I can probably still publish a story in Topbike on the odd occasion. Most of my freelance writing will be for Citibike, a motorcycling supplement for the Johannesburg-based, daily newspaper The Citizen, every Tuesday.

In a weird way, this is still my dreamjob. It will be forever. It’s just that it came at a cost that was too high. And I wasn’t willing to pay that price. Even for my dreamjob. Its a bit like a woman that you love to bits, but when you are together things turn messy – you just can’t get along. See my post 6 month ago.

Going back to freelancing gives me the freedom to publish my own stories when I want, how I want. If I want. It won’t be more than two or three stories a month, and the important factor is that it should be fun. Otherwise there is no point.

Since the Citibike crew has first option on testing new bikes, I will focus on lifestyle features, like trips and events.

I am moving back into trying to save the world (sustainable development), as I have done at the University of Cape Town. It is with ZaGroup (www.zagroup.co.za), a bunch of marketers with heart. My kind of people.

Wish me luck

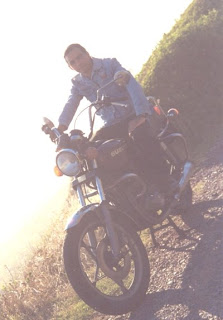

My friend Riaan

The fact that it was an unregistered import from Lesotho and that the bike has been standing in a garage for 10years was beside the point. Riaan has a bike, and that is all that matters. Now there would be three of us easy-riding through the Cape’s mountain passes and beach roads.

Well, it was actually up to handy-man Eddie to come to the rescue as usual and sort the bike out. Which he did. To my surprise. Couldn’t believe it when he got the thing starting with a loud bang in a cloud of black smoke. He spent almost a whole day stripping, cleaning and putting together the carbs. Good man, this Eddie.

And that same night Riaan had his first ride. Knowing how reckless and over-confident Riaan can be, I was a bit scared for his sake. I don’t refer to him as a loose canon without reason; mechanical things, especially computers and cameras, just seem to break automatically when he walks into the room. What he doesn’t destroy he looses. Will it be the same with his bike? It turned out to be ok; he got the hang of the working of the controls and balancing the bike predictably quickly. He was always a very fast learner. The XL has quite a snappy throttle action (great for wheelies!), but even that did not faze Riaan. He spent learning the ropes late into the evening.

And that same night Riaan had his first ride. Knowing how reckless and over-confident Riaan can be, I was a bit scared for his sake. I don’t refer to him as a loose canon without reason; mechanical things, especially computers and cameras, just seem to break automatically when he walks into the room. What he doesn’t destroy he looses. Will it be the same with his bike? It turned out to be ok; he got the hang of the working of the controls and balancing the bike predictably quickly. He was always a very fast learner. The XL has quite a snappy throttle action (great for wheelies!), but even that did not faze Riaan. He spent learning the ropes late into the evening.The next morning he ventured into the traffic, and my other concern got dispelled. He also learned quickly how to place himself on the road with regard to other vehicles, and “read” the traffic. Within days he behaved like a seasoned commuter, blending in with the daily rush.

And pretty soon as well, the bike was too slow for him; he wished for more power – always a good sign. Or a bad one, if you are his mother.

But Riaan responded in anger; no-one ever mentioned anything about checking oil-levels and topping up the oil to him. All he did was throw in petrol and ride; day after day. That was another expensive lesson to learn.

Still another lesson was waiting in the wings; learning about the dishonesty of bike mechanics. Said workshop had his bike in pieces for 3 or 4 months, having extolled the money for the job from him before the time, and not delivering. Riaan eventually carried his bike away in boxes to another workshop in the city centre. Needles to say, service is not much better. It’s been almost a year now since his bike seized and he is still waiting for it to be delivered.

In the mean-time, Riaan upgraded to a BMW R75; a bike that has the power and image best suited to his artistic and unconventional nature. It wasn’t a promising start either; the bike came with non-standard Keihin carburators and only after many more (dishonest) workshops and thousands of rands, he got the bike running.

But he is very happy with his bike at the moment; enjoying every sound and vibration.

Riaan was actually the first of us to take the long road solo; he rode a five hour trip to Victoria-Wes in the middle of the Karoo. A more comfortable tourer you can’t get; and from Victoria-Wes he has the rest of the sub-continent in mind: he is taking the long way back home.

The Bee-em got stolen right in front of my home in broad daylight with no-one seeing a thing. Having a soft spot for old bikes, he got a rare Suzuki GS850L. He has already criss-crossed the lenght and breath of the country on it.

My friend Eddie

It is with his GS and my GSX400FW that we had the best riding times together. The GS and GSX were a perfect couple; different in power, performance and design, yet evenly matched in spirit and attitude. These were the bikes and times we cut our riding teeth on; exploring our new-found freedom; easy-rider style, up the west-coast and through the Boland.

It is with his GS and my GSX400FW that we had the best riding times together. The GS and GSX were a perfect couple; different in power, performance and design, yet evenly matched in spirit and attitude. These were the bikes and times we cut our riding teeth on; exploring our new-found freedom; easy-rider style, up the west-coast and through the Boland. Eddie has good mechanical aptitude, and he keeps his hand on the minor stuff in looking after his machine. And sometimes he even has to help out on our (Riaan and I) bikes.

Eddie has good mechanical aptitude, and he keeps his hand on the minor stuff in looking after his machine. And sometimes he even has to help out on our (Riaan and I) bikes. Eddie fell in love with Suzuki’s Bandit 400 early on in his biking life. Even while he still had the GS, he bought the Bandit. It was a mixed experience; fraught with difficulty from day one. It suffered a seemingly irrepairable electrical glitch that caused it to cut out, even at high speeds.

Eddie fell in love with Suzuki’s Bandit 400 early on in his biking life. Even while he still had the GS, he bought the Bandit. It was a mixed experience; fraught with difficulty from day one. It suffered a seemingly irrepairable electrical glitch that caused it to cut out, even at high speeds. And this caused him the most serious accident he ever had (and he had a few). One evening, I was way ahead on the highway, trying to outdrag him (by this time I had the GS500E). After a few moments I realised he was no longer behind me, and pulled of, waiting for him to catch up. When I realised he was not coming I got worried. A car stopped behind me, the driver got out and asked if I have a friend on a bike behind. My heart sank. He told me my friend had an accident.

And this caused him the most serious accident he ever had (and he had a few). One evening, I was way ahead on the highway, trying to outdrag him (by this time I had the GS500E). After a few moments I realised he was no longer behind me, and pulled of, waiting for him to catch up. When I realised he was not coming I got worried. A car stopped behind me, the driver got out and asked if I have a friend on a bike behind. My heart sank. He told me my friend had an accident. I turned back, and arrived on the scene in the midst of flashing blue, red and orange lights. The high-way was backed-up, and my stomach heavy with doom. I did not want to see what I was about to see.

I turned back, and arrived on the scene in the midst of flashing blue, red and orange lights. The high-way was backed-up, and my stomach heavy with doom. I did not want to see what I was about to see.

The bike was an insurance write-off, but most of it was remarkably intact. The point of impact from behind seemed to be the exhaust, followed by the wheel, swing-arm and subframe. This left the engine and front-end undamaged. So Eddie bought the bike back from the insurance company, bought a frame, and had a Bandit again.

But the bike was not the same ride again, least of all because that electrical gremlin remained. So he sold it.

His old GS was on its last legs, so that had to be put down (literally!) as well, but that is another story…

The XT is now doing service as a back-up to the lovely Bandit 400 Limited that he took ownership off. It is a stunning looking machine, with a really mean and intimidating exhaust note.

The big snake

Snakes are of some significance in the culture of the Khoi and San people of Southern Africa. Being nomadic people, they would cover vast areas of the sub-continent in their travels. Water was of course crucial to survival and they believed some rivers, fountains, dams, etc. to be guarded by a snake. They were fearful and respectful to snakes and would then have to please it to gain access to the drinking hole. This might have been achieved in several ways, most probably by singing to please the creature. Such non-aggressive behaviour would relax the snake, prompting it to make way for the visitors.

As a toddler, I used to gather wood with my grandmother in the rather dry, rocky plains around O’kiep, Namaqualand. One such hot midday, we noticed a spiral of dust accompanied by a huge noise, almost like the drown of a small truck ahead of us. We thought it to be a truck, but were puzzled to find that it travelled transversely to the road, and in fact, crossed it at some point ahead of us. We took no further notice, but as we walked, came to the point where this noise and dust crossed the road.

I still chill by the thought of what I saw. Being a gravel road, we could see the markings clearly; the fresh track of a snake about 30cm in diameter, carved deep into the sand. Where it left the road, the bush was divided violently in half as it forced its way through at speed. There was no track going around the big rocks either. It seems to have crossed them right over. Clearly one mean, bad-tampered bastard. I wanted to follow it badly, but fear paralysed me. We stepped over the track, careful not to touch it, and headed for home very quickly. Now the noise and dust could have been a normal whirl-wind, but that still leaves one very big snake. I know what I saw.

I still chill by the thought of what I saw. Being a gravel road, we could see the markings clearly; the fresh track of a snake about 30cm in diameter, carved deep into the sand. Where it left the road, the bush was divided violently in half as it forced its way through at speed. There was no track going around the big rocks either. It seems to have crossed them right over. Clearly one mean, bad-tampered bastard. I wanted to follow it badly, but fear paralysed me. We stepped over the track, careful not to touch it, and headed for home very quickly. Now the noise and dust could have been a normal whirl-wind, but that still leaves one very big snake. I know what I saw.The flying snake, or the "Great Snake" as it is more commonly known amongst the people, has been an integral part of the Khoi and San tales and folklore for probably as long as they existed. Stories of regular sightings are common even today. Accounts vary from a big snake with a diamond on its forehead that shines at night, to one playing enjoyable music and changing into a seductive person of the opposite sex to lure its unfortunate prey. It seems to reside at watersides and mountains. It changes into a strong, destructive whirlwind when migrating over long distances, causing havoc on the way. People would throw salt over the roof of their dwellings if they notice it to be in the path of this harmful force. This would gain them some sort of protection. A demonic connotation to this snake is always apparent.

Sightings of the "Flying Snake" or "Big Snake" is a common occurence even today.

Sightings of the "Flying Snake" or "Big Snake" is a common occurence even today.Like all legends and mythical tales, it probably started as a true story, and with generations of retelling, the truth got muddled with vivid imaginations. Or so I hope, with the great snake. When visiting Namaqualand, I would still take regular walks in the field, hoping see that track again, or even the devilish creature itself. I don't know if it will be a lucky or unfortunate encounter.

- originally published on www.woza.co.za (Woza was a brilliant, independent news website, which has sadly closed down due to funding difficulties).

11 February 2003

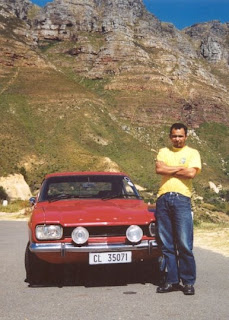

11 February 2003The Car-mad Namas

Like last time, this was also a nostalgic trip, but with a difference. This was a trip about coming to terms with my childhood, making new memories, bonding with an estranged family, and most of all, having fun.

And fun I had. My car-mad, twenty-year old nephew, Heinie, is quite a sight to behold behind a wheel. His car-mad dad has had the same impact on him now as he did on me in the seventies. All he can talk about is cars and bikes. And the real revelation was how car-mad the rest of his friends are. If I wasn’t a petrol head myself, I would have fled their company long ago.

And fun I had. My car-mad, twenty-year old nephew, Heinie, is quite a sight to behold behind a wheel. His car-mad dad has had the same impact on him now as he did on me in the seventies. All he can talk about is cars and bikes. And the real revelation was how car-mad the rest of his friends are. If I wasn’t a petrol head myself, I would have fled their company long ago.

The highlight of the visit was me and Heinie dicing (with his father’s BMW 325i) with a BMW Shadowline 2.7 through the main street in Concordia. The Shadowline driver could not get past us and threw in the towel as we hooked up fourth gear!

The Saturday night there was a promise of a dice between a guy from Springbok with a turbo-charged Nissan 1400 bakkie, and a youngster with a normally aspirated, ported and gas-flowed Honda Ballade. It was a disappointed to find that we arrived too late for the dice, but I was even more horrified to learn that the Honda won. I was so sure the turbo-Nissan would have it for supper. Would have lost money on that one! We met up with them after the dice, the Honda still ticking hot and in need of oil. They were rather shy about where all that speed was coming from, and both the car and the engine looked dissappointingly "standard". As the car sped off, it was an unbelievable sight to see the exhaust spewing flames with each gearchange.

There aren’t that many bikes in Namaqaland. I was looking forward to meeting Werner, a friend of Heinie living and working in Aggeneys that rides (apart from a customised Mark I Golf), a prestine looking Suzuki GSX-R750 Pre-sling. Werner was at work when I came around, so I stole a few snaps of his spotless bike instead.

There aren’t that many bikes in Namaqaland. I was looking forward to meeting Werner, a friend of Heinie living and working in Aggeneys that rides (apart from a customised Mark I Golf), a prestine looking Suzuki GSX-R750 Pre-sling. Werner was at work when I came around, so I stole a few snaps of his spotless bike instead.

We don’t really know each other that well, Heinie and I, as we never had a chance to spent time together with me being in Cape Town while he grew up. I remember him as a stubby toddler, and all of a sudden I have this youthful testerone-charged ex-school rugby captain staring down at me. So it was a time to begin a new chapter in our family. A chapter that promises great fun.

Perhaps, as a testimony to that promise, Boeta committed to fix my neglected BMW 525 for me, provided I can get it down to Namaqualand. I was considering putting the poor thing out its misery in some car graveyard. But Boeta went to show me an almost rust-free 525 tucked away in a yard in Okiep. Provided we can by that car, I would have one neat Bee-Em someday soon.

Boeta is quite a slave-driver, having to help him in his garden all day long, and with all the car-madness, it was a challenge to find time for some peace and quiet. I spent an afternoon tracing my favourite walks through the veld and koppies around Okiep, but felt a bit detached. I was gone for so long, yet it seems like I never left. The overwhelming sense was how small everything looks. The mountains are lower, the vast plains shrinked, walks that seemed to take hours takes minutes. In the end, it was perhaps just a tribute to the child I am leaving behind. Live has taken me to borders beyond what I could ever imagined as a barefooted kid roaming through this shrub-veld.

I did not spent all that much time with Ouma in Okiep. And maybe that is fine, as I formed new bonds with other family members. But it is shocking to see how old she is getting. And fooling around with Lucille’s two kids, well, they are too cute for words. They are where I was 30 years ago, well physically at least. The influences of those times in Okiep molded me into what I am today. I can only wonder about the experience they have at the moment. I can only hope I am a positive influence on them.

I did not spent all that much time with Ouma in Okiep. And maybe that is fine, as I formed new bonds with other family members. But it is shocking to see how old she is getting. And fooling around with Lucille’s two kids, well, they are too cute for words. They are where I was 30 years ago, well physically at least. The influences of those times in Okiep molded me into what I am today. I can only wonder about the experience they have at the moment. I can only hope I am a positive influence on them. 15 October 2004

15 October 2004A brief background of the Nama Revival in South Africa

The seriousness of this “reconscientisation” of the Nama's cultural lineage was highlighted in 1991 with the establishment of the Richtersveld National Park, in the farmost North-west corner of Namaqualand, next to the Namibian border. Only after 18 years of negotiations (read fighting) with the then apartheid government, did the Nama people (believed to be extinct by those in power for many years) allowed the establishment of a national park on their doorstep; the Richtersveld, which is South Africa’s only mountain desert.

But what was the problem? The National Party government of the time wanted to establish this conservation park in an area where the Nama people have being herding their goats and sheep for at least 2000 years – without consulting them! Moreover, the Nama people were to loose the right to let their stock graze in the area that would be confined by the park. Yet, nobody knew the plants, soil, wildlife, weather patterns, etc. better than them. So how could they not take part in the conservation process? Demonstrations and marches to parliament in Cape Town followed and eventually, the National Government gave up. Conservation was redefined, as was the international move at the time. Locally, the concept of Peoples and Parks was born; and probably South Africa’s first working example of eco-tourism. Proceedings from tourism are made available for community development while employment and entrepreneurial opportunities in the park raised the standard of living significantly.

Today, the struggle continues. For one, against a government that seem slow to acknowledge the concept of indigenous, or at least first peoples. There are distressing signals that, as before, the history of the Khoesan will once again be neglected – if not ignored - as the history books are rewritten. In the name of nation-building and political correctness it is seen as not conducive for a harmonious society to state that a particular group of people was here long before others.

Embracing this concept will also not only add extra vigour to the debate of “africaness”. Recognition of indigenous rights, which is defined separately from human rights, will open up access to land, education language of choice, self-regulation, etc. as is dictated by international convention. All of which is catered for to a large extent by our advanced constitution, but will still cost the government dearly in resources.

There is also the struggle to gain acceptance amongst our own co-descendants. The majority of Khoesan descendants, especially those in urban areas, want nothing to do with the issue, and identify exclusively with being coloured or brown. It is seen as “backwards” and something to be ashamed of. Those of mixed descendence will still talk with pride about the European part of their heritage. Never the Khoe or San part. So wider awareness and acceptance of the revival will take time – if ever. Decolonising the mind as they say. There is also the risk that the debate might become mainly the reserve of academics and intellectuals. At the moment, however, the balance seems healthy with activists represented by the poorest of communities.

Documentation of the history of the Khoesan is very sketchy, and thankfully, academics and sections of the media are doing their part. But as part of the revival there is also the individual need to go back and dig deep. Every bit of historic detail will contribute to the reconstruction of a past that almost went forgotten. Government has conducted a “status quo” report on the Khoesan, the result of which will influence the strategy the reconstruction will follow.

We are rounding the bend and there is no turning back.

Going back to my Nama roots

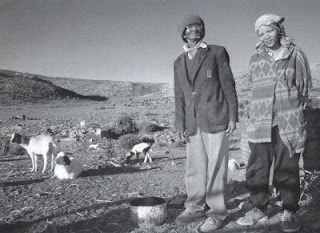

Through the Klipkoppiestreek (region of small, rocky hills) where I feasted on wild fruit like !khounibe (a wild berry with a dry, fruity taste), chasing rabbits barefoot through the kliprandjies (rocky edges in the landscape). Back among these familiar mountains I recall the sweet-sour odour of taaibos – and the days I spent grazing goats with my grandfather.

I am on a story that takes me to the heart of the Nama cultural revival. Today, close to end of the 20th century, the Khoe, and in particular the Nama people situated in the Richtersveld, are reclaiming their traditional ways. And they are staking their claim to the status of indigenous people.

Defining who indigenous people are is forbidding. Africans, as distinguished from white, Asian and so-called coloured people, can, and to some extent do, claim indigenous status.

Defining who indigenous people are is forbidding. Africans, as distinguished from white, Asian and so-called coloured people, can, and to some extent do, claim indigenous status.For this reason, Joe Little, Director of the Cape Cultural Heritage Development Council, uses the term First Nation rather than indigenous. The argument is based on archeological research that reveals the presence of San people at least 25 000 years ago. The Khoe (Nama, Gruiqua and Koranna) arrived later with their stock and Bantu-speaking people (the preferred term for black Africans used by historians and socio-linguists) following thereafter.